Ladakh (34.0o N 77.5o E) in northern India is a mountainous region, where the mainstay of the economy is agriculture and livestock (Ehlers and Kreutzmann, 2000) and where the temperature ranges from +35 C to -35 C. Despite the harsh climatic conditions, Ladakhis have managed to develop a remarkably productive agricultural system to meet their subsistence needs. Nonetheless, agriculture and livestock production have suffered in the last two decades due to factors such as new alternative livelihood opportunities such as tourism, climatic uncertainties, poor market linkages for local products, etc.

Changes in land use and livelihoods due to these factors may have serious implications for the long-term sustainability of Ladakh (Fox et al., 1994). Through ages, people in Ladakh have survived by practicing indigenous traditional knowledge passed on by our ancestors-be it agriculture, pastoralism or handicraft. However, with the advent of development in the form of infrastructure, alternative livelihoods, jobs and services, technology, etc. dependence on traditional livelihood such as agriculture and pastoralism have reduced significantly and along with this the application of traditional knowledge has come down. If  we are to preserve and

we are to preserve and

promote the cultivation of

indigenous crops and knowledge

associated with these, it is

imperative that we talk, consult and

document the elderly in the villages.

Based on the knowledge shared and

inputs given by the elderly,

participatory plant breeding could

be initiated to bring out the

desirable characters in a particular

crop.

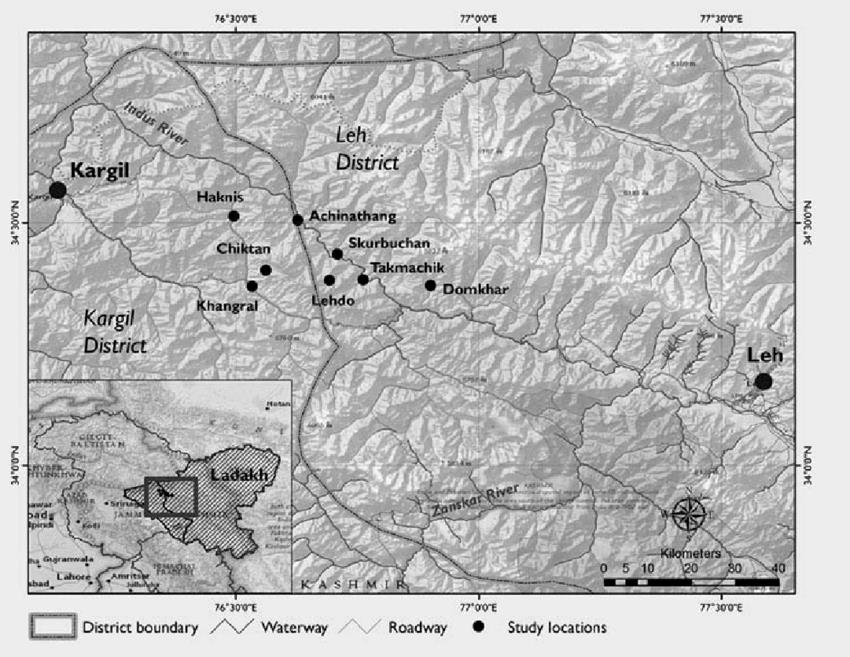

Project area

Takmachik (34.28o N 76.76o E) is village in western Ladakh, situated at a distance of about 110 km from Leh town. The village has 65 households with a population of around 450 people and is situated at an altitude of about 2900 m above sea level. The climate is arid type with scanty and erratic precipitation (80mm per annum) and temperature ranges from +35 to -20 oC. The village is well vegetated with orchards, willow and poplar. The villagers are mostly farmers, growing crops such as barley, buckwheat, wheat, pea, vegetables, and mustard. Takmachik is the first and only organically certified village in Ladakh and its products such as apricots, apricot oil, walnuts and buckwheat are very popular nationally.

Urbis (34.16o N 76.46o E) is also a village in western Ladakh, located in a gorge at a distance of about 130 km from Leh town. The village has 25 households with a population of around 150 people and is situated at an altitude of about 3200 m above sea level. The climate is arid type with scanty and erratic precipitation (80mm per annum) and temperature ranges from +30 to – 25 oC. The village is well vegetated with orchards, willow and poplar. The villagers are mostly farmers, growing crops such as barley, wheat, pea, vegetables, and mustard. The village is also very popular for its high-quality local peas, apricots and walnuts.

Problem statement

A quick review of the literature reveals that there has not been any apparent effort to engage local farmers and value their traditional knowledge to preserve and promote indigenous crops by any agency in Ladakh. Therefore, Vishwadeep Trust under the National Mission on Himalayan Studies funded by Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has conducted a baseline survey in Takmachik and Urbis to gather information on the status of farmers understanding and knowledge on local crops, its promotion and preservation, the concept of seed banks, constraints in agriculture production, public and private sector interventions, etc., as an attempt to build a baseline for conducting Participatory Plant Breeding.

Rationale

Participatory plant breeding is important because not only does it help ensure that new varieties are directly meeting farmers’ needs, it also educates and empowers farmers to be part of the breeding process, giving them the tools they need to begin new breeding projects. Moreover, including farmers improves the process because the farmers know what priorities they have for a variety e.g., in case of apricot it is sweetness, kernel oil content, shelf- life, maturity, disease resistance, yield, etc. They know what their markets will accept. Also, involving farmers increases the likelihood that the variety will be adopted when it is released since the farmers are already invested in the project.

Objectives

To understand the socio-economic and demographic context of the farming community.

To understand the traditional knowledge of the area, especially regarding the use of variety, seed, and processing management of these crops. To understand the type of crops (cereals, oilseeds, pulses, fruits, vegetables) under cultivation. To assess farmers’ knowledge and interest in participatory plant breeding and in establishing seed bank. To assess the scope of collaboration with other concerned government and non- governmental agencies. To assess present challenges in production of cultivated crops.

Methodology A semi-structured approach to interview key respondents from the two villages was used to collect primary data. The study population consists of locals-male and female from both the village. Ten key respondents were selected based on their involvement with agriculture and horticulture. However, before starting the interview, consent was sought from each respondent on their willingness on engaging in the interview. Demographic data for each village were gathered from the head/Nambardar of the village. Given the time and financial constraints, 10- 15% of the households in each village were surveyed. Secondary information from related publications, reports and articles were used. We also intended to use Participatory Rural Appraisal tools to understand preliminary understanding of the local context and the information generated from PRA were supposed to be used as a complementary data source to consolidate the baseline findings. However, due to covid-19 related restrictions imposed by government of UT Ladakh, this could not be done. Additionally, to further strengthen the study, focus group discussion at ward-level were planned to collect information regarding the local cropping system, crop diversity, seed management practice, and processing equipment. Survey questionnaire Primary data were obtained through a questionnaire survey carried out in the month of December 2020 (Appendix A). The questions were focused mainly on themes associated with participatory plant breeding such as crops under cultivation, seeds, capacity building training, constraints/challenges in agriculture, dependence on agriculture, acreage under cultivation.

Field work

Considering the great deal of remoteness and time constraint because of challenges

posed by covid-19, we took help from locally hired volunteers. However, prior to the data collection, they were properly trained and oriented, on survey procedures such as how to interact with the respondents, how try not to influence the responses and how to record the responses. Data analysis Since there is no baseline data available to do a comparative study on farmers’ perception, involvement and understanding on participatory plant breeding, therefore the results from this study can be used as a baseline for future studies. Moreover, due to small sample size because of time constraint we could use any statistical tool to analyze the data. Questionnaire preparation and pre-testing The questionnaire survey was prepared by reviewing questionnaires of other similar projects. The drafted questionnaire was shared with the Principal Investigator for reviewing and commenting and accordingly refined by incorporating the suggestions. Administration of the Survey The questionnaire survey was carried out by the Junio Project Fellow along with two locally hired volunteers. The JPF and volunteers were given orientation on the questionnaire content, data recording, sampling, and interviewing method and process by the Senior Research Fellow, who had the experience of already conducted baseline surveys in the field. At the end of each interview day, the survey team jointly cross checked the data collected in the field to minimize the effects of any response and recording errors. Due to the remoteness of the survey site, immediate data entry into a digital spreadsheet in the field was not possible.

Data entry and cleaning

Data entry was completed by the SRF and JPF. Afterward, data were cleaned using Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Results

Family members engaged in agricultural activities: On an average 4 members in Takmachik and 5 members in Urbis in a family are engaged in different phases of agriculture process.

Major source of income: As stated earlier, other than service sector, majority of the respondents from both the village generate some income from agriculture and horticulture. Land and acreage under cultivation: On an average, a household in Takmachik owns 9.7 kanal of land of which more than 85% is used for cultivation, where in Urbis, it is more than 12 kanal per household of which close to 70% is used for cultivation. The land holding in Tkamachik ranges from 2 kanal to 15 kanal, whereas in Urbis it is between 6-20 kanal. Sustenance from own grown foods in a year: From the survey, it became clear that Takmachik being an organic village has more land under cultivation at a household level. This could be a reason for the villagers sustaining for longer months on their own produced foods compared to Urbis where although the land holding is bigger but area under cultivation is smaller than Takmachik. Type of cereals, pulses, fruits, vegetables and oilseeds: owing to their altitudinal difference, the two villages differ slightly in the type of crops they grow. For example, Takmachik being at lower altitude, grows buckwheat, fruits such as peach, cherry, pear, etc., at larger scale, where as Urbis being at higher altitude grows local peas at commercial scale. However, cereals such as barley and wheat are common in both the villages. In terms of oilseeds, both the villages grow mustard for subsistence need. With regard to vegetables, both the villages grow more or less the same vegetables such as cabbage, onion, carrot, tomatoes, leafy, etc. Training and capacity building: With regard to training on breeding techniques such as selection and cross breeding to improve existing varieties, none of the interviewed farmers from both the villages received any training from government or private agency. However, two respondents from Takmachik and four from Urbis did receive training on propagation techniques such as grafting, budding and layering. The respondents from both the villages are of the opinion that capacity building and awareness on breeding and propagation have increased lately. Local indigenous crop that needs preservation and promotion: Majority of the respondents (90%) from Takmachik showed their interest in promoting and preserving buckwheat followed by barley. The reason behind choosing buckwheat could be its short growing season, it is grown as a second crop after barley or wheat coupled with growing demand in the market owing to its health benefits. Whereas in Urbis, a large section of the respondents are interested in promoting and preserving barley followed by local peas. The cultivation of local peas is practiced only in few villages in Ladakh and Urbis is one of them. Considering the long shelf life, high nutritive value and its potential in creating new products of added value, local peas genuinely needs promotion and preservation. Familiarity with participatory plant breeding: ninety percent of the respondents from both the villages have never heard of participatory plant breeding. Whereas, none of the respondents from either village have taken part in participatory plant breeding ever. In Takmachik, the respondents are interested in conducting participatory plant breeding on buckwheat because of its high market demand and health benefits, whereas in Urbis, respondents showed their interest in conducting participatory plant breeding on wheat followed by barley. The reason behind opting for wheat could be that until recently Ladakhis were largely dependent on the Public Distribution System (PDS) for meeting their needs for wheat however lately PDS has started rationing wheat distribution on the basis of per member per family. Since,

wheat is a staple in Ladakh, rationing does not meet the whole demand of a family, hence, growing it in their own fields is the only option left. Community seed bank: A close to 90% of the respondents have never heard about community seed banks and none of the village has one. There could be multiple reasons for this, however, the primary reason could be a lack of awareness on the need and importance of having one. Concerned government departments and private agencies such as NGOs and seed companies can play a key role in mobilizing people on the need of establishing a seed bank at village or constituency level. At present majority of the respondents from both the villages use their self-saved seeds for next season sowing, exchange of seeds with neighbors, relatives or from other villages is also common. Government also help supplement the requirement of seeds especially for new crops. According to the survey, most of the respondents also do not employ good practices for seed storage. Hence, establishing a community seed bank would be helpful to address this constraint as it can improve the local availability of quality seeds of local crops. Crop diversity: We got mixed responses from both the villages on assessing the state of diversity of crops in the villages in the last ten years. However, they were not able to clearly recollect which crop? Additionally, the respondents are not aware of any plans or initiatives by UT Ladakh on assessment genetic diversity of cultivated crops in their villages. Similarly, none of the respondents are aware of any procedures in place to monitor or measure genetic erosion by UT Ladakh. Nevertheless, almost 50% of the respondents from both the villages reported changing varieties of crops such as wheat and potatoes in the last ten years for increased yield. All the respondents from Takmachik tells that the government and local NGOs have taken initiatives in introducing market to their products especially buckwheat, apricots and watermelon. Similarly, the respondents from Urbis mentions that action is being taken by the government in introducing them to new crops such as watermelon and also initiatives to encourage the continued cultivation of local peas. However, they do not know of any documents in the form of data, pictures, videos, etc. that could act as a testimony to the actions and interventions taken for preservation and maintenance of indigenous varieties in the past ten years. Existing production constraints in cultivated crops: At present, the biggest production constraint in both the villages is low external inputs and services such as compost and farm yard manure. This problem is bound to surface because lately farmers have significantly reduced rearing livestock especially goat and sheep, whose manure is considered as the best for Ladakh’s agro-climatic condition. Regarding compost, the preparation know-how knowledge is lacking among many farmers and even if one knows about compost making, not meeting the ideal physical conditions such as optimal temperature and humidity act as hindrances in making compost. The second constraint is shortage of man power as a result of migration. Since, agriculture in still very subsistence, scaling up for commercial purpose comes with lots of challenges such as poor market linkages, subsidized ration from PDS, younger generation not opting farming as a career, etc. All these result in youth and male members of the family migrating to Leh or other metro cities such as Delhi, Chandigarh, Jammu in search of better paying work and to pursue higher education. Additionally, labour shortage as a result of migration has led to a decrease in area of cultivation of local crops and an increased workload on female farmers and non-migrating family members. Introduction of labour efficient cultivation and processing technologies such as solar dryers will help to grow and utilize local crops. Climate change, pest and disease are other constraints in production especially in Urbis village.

Discussion

Majority of the respondents voiced for the need of promotional and preservation work on indigenous crops from both the villages, whereas some do not seem interested in it. Among respondents showing interest in preservation of local crops, majority chose buckwheat in Takmachik and barley and local peas in Urbis. These are also the crops on which the respondents are interested in conducting participatory plant breeding. Buckwheat in Takmachik

and local peas in Urbis have great potential not only in high production as local crops but also in

generating additional income for the farmers especially buckwheat owing to its high market demand and health benefits. On the other hand, local peas, also very nutritive is currently being neglected by farmers because it has not been promoted for the right reasons. Hence, in order to boost demand for local peas, it is important to create market linkages at both local and national level. Despite key role of local crops in meeting food and nutrition security, religious and cultural requirements, their hardiness and resilient to stresses especially cold and low humidity investment in research and development from public and private sector has not been satisfactory. Without involvement of governmental agencies, the conservation and promotion of local crops cannot be mainstreamed. Since a large number of rural families still rely on these crops despite their hardships, it is important for the government research and extension sectors to alleviate the rudimentary constraints that are holding these crops back. Policy advocacy is needed to mobilize changes in regional and national policies, strategies and plans. Potential opportunities There are several good opportunities of promoting of local crops through sensitization, value addition and developing market linkages. For example, in the case of buckwheat, considering its health and economic benefits, there is huge possibility of identification of most promising varieties in terms of production, disease and climatic stress tolerant trait. Moreover, in addition to the existing local recipes that are made out buckwheat, new recipes such as cake, dosa, soup, tea, etc can be introduced as an attempt to develop new products. Since participatory plant breeding is a participatory approach, there is great scope in collaborating with local research centres, farmers, extension workers to develop varieties of preferred traits. For example, in case of apricots, working on traits such as increased shelf-life, sweetness, and oil content of kernels can be initiated. This will help in value addition and accordingly its marketing can be done with local branding. As both the villages are connected with road network up to Leh town, viable renewable technology introduction, local product transportation and developing market linkage is economic, reliable and full of scopes. Since Leh town attracts a lot of tourists during the summer, local products with value addition and branding can have good marketing opportunity by linking with tourism sectors particularly with hotels, home stays and souvenir shops. An awareness raising and knowledge dissemination regarding local crop conservation and marketing can be done via local radio and TV networks and social media for wider dissemination.

Recommendations

Identification, registration and characterization of promising local crops should be a top priority at the beginning of the project. Local crop inventory and archives should me made and properly documented. Rare varieties of local crops should be restored to prevent them from being extinct through community seed banks. Farmer preference for these varieties can be assessed using participatory selection of varieties with desirable traits. Widening seed exchange network and improving technical aspects on seed selection and proper storage should be on priority work of the concerned stakeholders. Awareness raising on seed management along with viable yet renewable technology introduction of drying, cleaning, sorting and storage would be relevant. Product diversification through new product development initiative and value addition should be used to maximize utilization and marketing of local products. Local branding and authentic labeling of value-added products have great potential in attracting loyal customers. Social capital building: Social capital building is the most essential part to sustain project’s intervention for longer term. Capacity enhancement of technical farming, strengthening organizational management skills of local organization and regular technical support are very crucial. Without participation and ownership of the local community, interventions cannot be sustained. Since this project is first of its kind in Takmachik and Urbis regarding conservation and promotion of local crops through participatory plant breeding, it needs to invest significant effort on community sensitization. Along with raising awareness through different local activities like school programmes, farmer visits to experimental trials, organizing diversity fair, providing platforms for farmers to learn and share their knowledge will be helpful. Developing linkage and coordination among local stakeholders: To mainstream the project findings and interventions, effective mechanism of local stakeholder’s involvement and mobilization has to be developed. Also, conducting studies involving volunteers/youth can add value to the project’s outreach and knowledge dissemination. Coordination with local stakeholders is crucial on leveraging resource to support project activity implementation and to create synergic impact. Linking farming community at regional and national level will enable to develop sustainable mechanism to continue project’s intervention even after the phase out of the project. Maintaining data records and documentation are essential in any type project. Internal as well as external sharing of those documents will be helpful for efficient planning and maintaining work accountability. New findings should be shared with community and related stakeholders to demonstrate the relevance of work and maintain transparency. Sharing of knowledge and findings also help in providing motivation and insights for new innovations. Wider sharing of documented materials and findings also help to demonstrate project’s impact/achievements in real ground. In addition, proper documentation of minutes of community mobilization and consultation meetings, field reports and progress reports etc. and timely sharing with concerned stakeholders including farmers is important to maintain accountability and compliance.

References

Bhatia, S. Redpath, S. Suryawanshi, K. and Mishra, C. (2016). The relationship between religion

and attitudes toward large carnivores in Northern India. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 22(1):1-

13. Ehlers, E. and H. Kreutzmann (2000). High mountain ecology and economy: potential and

constraints. High Mountain Pastoralism in Northern Pakistan 132: 9-36. Eyzaguirre, P. and M. Iwanaga. (1996). Participatory plant breeding. Proceedings of a workshop on participatory plant breeding, 26-29 July 1995, Wageningen, The Netherlands. IPGRI, Rome,

Italy Fox, J. L., C. Nurbu, S. Bhatt and A. Chandola (1994). Wildlife conservation and land-use changes in the Transhimalayan region of Ladakh, India. Mountain Research and Development

14(1): 39-60.

Halewood M, Deupmann P, Sthapit B, Vernooy R and Ceccarelli S. (2007). Participatory plant breeding to promote Farmers’ Rights. Biodiversity International, Rome, Italy. 7 pp Pudasaini N, SR Sthapit, D Gauchan, B Bhandari, BK Joshi and BR Sthapit (2016). Baseline Survey Report: I. Jungu, Dolakha. Integrating Traditional Crop Genetic Diversity into Technology: Using a Biodiversity Portfolio Approach to Buffer against Unpredictable. Environmental Change in the Nepal Himalayas. LI-BIRD, NARC and Biodiversity International, Pokhara, Nepal. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and nation/govt-releases-maps-of-uts-of- jk-ladakh-map-of-india-depicting-new uts/articleshow/71868357.cms