Smart water management in high elevation villages to transform them into a vibrant land-based economy with diversity of crops grown.

Article under the project “Solar technology for post-harvest processes and sustainable agriculture for income

enhancement of tribal communities living in Cold Desert Region of Ladakh Kargil” NMHS 2020-21_MG80-11

Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change.

Keywords: Conservation, Ladakh, purification, Chhorpun, Conservation, International water treaty,

Indus, China

Ladakh is the roof of the world and a cold desert region which faces acute scarcity of water and

untimely supply. With rapid development as a result of U.T. creation, there has been an incessant

breaking of mountains, habitat loss which is increasing the degradation of land and causing water

shortage. The use of chemicals in agriculture, livestock rearing is a common cause of water loss.

Ladakh is 17000 feet above sea level, with great divides between eastern and western Ladakh in

terms of landscape and distance. Ladakh has been a victim of water scarcity partly also because of

the International water treaty of River Indus which flows between China and Pakistan but there is little

access to local population of Ladakh. Therefore, the Indus river doesn’t contribute to agriculture but

hydroelectric projects except for shey and Thiksey where they draw water from river Indus. According

to Dr. Enoch Spalbar, 80% of Leh water comes from Indus and in Choglamsar it is extracted through

borewell. Choglamsar has some great places of worship with great monks.

Chhorpun is the traditional water conservation and preservation system it is dependent on glaciers

melted water which is also not getting recharged due to climate change and incessant mountain

breaking. The usage of water was very well defined in terms of who and how people will get water

that led to reducing wastage. Chhorpun also reduces the problem of difference in height of carrying

water in high elevation villages. There is a traditional system in Maharashtra it is known as

Bandharas. The ahar and pyne systems of Bihar where an unlined inundation canal (pyne) transfers

water from a stream into a catchment basin (ahar), also evolved from a riparian doctrine. Unlike

modern sone canals built by the British, which have failed to meet the needs of the people, the ahars

and pynes still provide water to peasants. Early riparian principles were based on the notion of

sharing and conserving water. They were not attached to property rights.

There are huge restrictions on organizations trying to work on the subject; hence water crisis is a

huge impediment to livestock, livelihoods, and agricultural production.

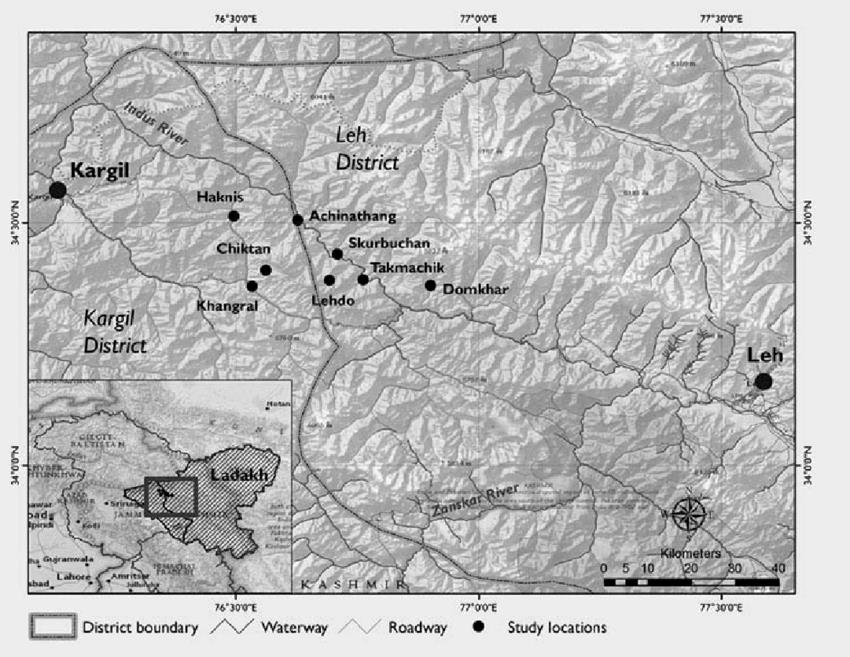

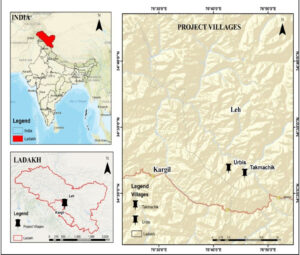

Takmachik is a village on the plateau opposite the road, leading to Kargil via Dah-Hanu belt along the

Indus river. Unfortunately, despite its location on the bank of a river, Takmachik faces shortage of

water for irrigation. The glacier is small and unable to feed the village with enough water, particularly if

there is low precipitation. As such, the limited water available through springs is an important source,

managed carefully.

An artificial glacier, constructed in 2016, is expected to provide some help, however, it is more like a

bandage solution and has attracted great publicity and international attention. I don’t think it is a

consistent and reliable solution. The village was provided by floating water pumps twice in three years

which burnt out, the cost of repair of each pump was 92,000/- and burn out time within a period of one

to two years. Due to the damage in the pumps during COVID-19, the water level is also constantly

rising up and down with no responsible person to monitor it and the pump was not submerged in

water fully, we need a water level indicator to see the flow and timely sensor alarm for switching it on

and off. In Domkhar, which has approximately 60 households, the population is dependent on glacier

water.

Recently in Takmachik, avid social workers climbed ice stupa of height around 85 feet without having

all necessary tools to hoist the tricolor when temperature falls to -15 degrees Celsius during the day.

This stupa stores million liters of water in freezing state during winters when it is of no use. Hence, it

can be used in spring season for irrigation purposes. The principle used here is gravita.

Please find bits about our work in the regions:

Takmachik: Takmachik is a village situated at an altitude of 2980 mt at a distance of around 130 km

from Leh town. The village consists of around 60 families which are mostly dependent on agriculture

economically.

Agriculture in Takmachik: In the past 10 years organic agriculture has been preached by various

NGO’s and government organizations which have been adopted by the villager at large. It is, in fact,

the only village in Leh district which can be called an organic village and their produce is becoming

famous every year. Apricot is a major source of income in the region and every household has an

average of 25 to 30 apricot trees. Apart from apricots recently different fruits like apple, cherry, and

plum have become very popular watermelon being the most predominant one. Usually, in the Ladakh

region, single cropping system is practiced but, in the areas, with lower altitudes, two products are

grown.

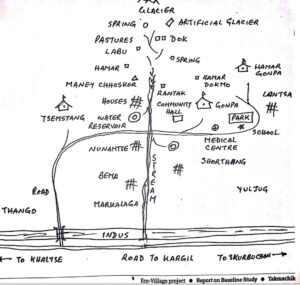

Current Scenario of Water in Takmachik: the main source of water for both agricultural practices

and drinking is spring water. Traditionally the village was reported to have three springs, but in recent

time’s two of them have dried off, majorly due to floods which have been happening in the past few

years. With recent development in agricultural practices in the region, and the water sources in the

area depleting, major water stress is being observed in the region. Some major interventions are

being introduced in the region one of which being the lifting of water from the Indus by floating pumps.

Traditionally there are three ponds in the village but at the moment only one is functioning. One of the

ponds was damaged in the 2014 floods and has not been repaired. The pond which is working

supplies water to the entire village. Water is lifted from Indus River and stored in the pond, which is

further used for irrigation. On average two families get to turn to irrigate their fields every 10 days. The

major water stress is observed during the second cropping.

Water Conservation Interventions required:

Ladakh has traditionally always depended on

agriculture economically, and so is the case in Takmachik village. But, in recent years a shift from

agronomic cultivation towards horticultural practices is being observed. People of the village are

growing more and more water-consuming crops like watermelon etc. which is resulting in a huge

increase in demand for water supply, but also at the same time the sources of water are drying up.

Therefore, now to meet the demand of the village, water from the Indus River is being lifted for

irrigation purposes.

Future Interventions required:

During the field visit we found that the motor was burnt due to dry run because of the

fluctuating water level, and suggested that a small reservoir needs to be built near the bay of

Indus where the whole setup is installed, this will prevent the motor from future dry runs and thus protecting the motor from fluctuating water levels otherwise, the villagers need to detail

a person to check the water levels and thus adjusting the submersible motor to prevent

future dry runs.

Therefore, to meet the future demand for water in the village some innovative interventions are being

practiced, but in the next few years the requirement for water will increase. Therefore, to meet those

challenges some innovations are required urgently.

At present there is only one pond out of the three that is functioning. The other two ponds are

damaged due to floods and need repairing. If all the three ponds are functioning then wastage of

water will be minimal and also due to the lifting of water from Indus, the frequency for irrigation which

at present is 2 households per 10 days, it can be brought own to maybe 6 days.

Pond lining in all three ponds should be done to prevent loss through seepage.

The floating pump which has been installed should be of one with higher liters per second.

Mulching is an important and effective technique to prevent water loss. It should be preached, and

also adopted by villagers for vegetable production.

Urbis village: It’s a village situated around 150 km from Leh town. It’s a small village nestled

between the hills. There are a total of 17 to 20 families settled in the area.

Agriculture in Urbis: Urbis village has always stayed away from chemical fertilizers. Traditional

sustainable agricultural practices have been followed and are still being followed. Every household

holds an average of 4 domesticated animals which give them enough manure for agricultural

practices. In horticultural crops, walnut and apples were being grown from lime immortal but in recent

times apricot is also being grown. Apart from barley and wheat, pea, pulses, potato are also being

grown.

Current Scenario of Water in Urbis: the main source of water in the village is the small glacier which

is located about 5 to 7 km from the village in the hills. The amount of water being discharged from the

glacier has been reducing year by year, due to the reduced snowfall which recharges the glaciers.

There are no ponds to store the water which are generally found in most of the villages.

Water Conservation Interventions required: Due to the changes in water availability agriculture is

also being affected. The major problem arises during the springtime when the 1st dose of water is

required.

Future Interventions required:

To cope with the scarcity of water in the village, it is suggested to tap

into the water resources which are available in the village. Apart from the glacial water, a spring

source of water is available in the lower area. This source is not used and the water is mostly wasted.

Constructing a pond near the spring and lifting the water during the time of water scarcity is

suggested.

Water and Crops:

There is very little training and awareness given on the kind of crops and the amount of water they

consuming at the time of sowing, reaping that is given to farmers. For instance watermelon and

eucalyptus requires a lot of water, barley needs more water, vegetables need less water. If we create

awareness and markets for the same like water mark or even a certification that this crop is water and

glacier friendly. Usually, the first harvest is dependent on spring water, melting ice and snow and their

second cycle of harvest is dependent on snowfall. We therefore, need to keep a check on increase in

size of glacier and climate change at the moment we have no alternative.

We should create a robust marketing, measuring and certification that goes beyond organic keeping

water conservation in mind. Ladakh till now didn’t have a weather department or climate change

centre; we have proposed to do both with several ministries. We also suggest a water information

management system that keeps in check the zings i.e. ponds in Ladakh and records the change in

size of artificial glaciers.

There is infestation due to water storage and collection in zings and some water reservoir tanks are

overflooded, very little is done to maintain proper hygiene and cleanliness.

Without water, food production is not possible, water scarcity translated into a decline of food

production and an increase in hunger. Traditionally, food cultures evolved as a response to the water

possibilities surrounding them.

In high altitude regions, pseudo cereals such as buckwheat provided nutrition. In the Ethiopian

highlands, teff became the staple of choice. In Ladakh Buckwheat known as bro is grown rampantly.

The water use efficiency of crops is influenced by their genetic variation. Maize, sorghum and millet

convert water into biological matter most efficiently. Millet not only requires less water than rice, it is

also drought resistant, withstanding up to 75 percent soil moisture depletion. Had agricultural

development taken water conservation into account, millet would not have been called a marginal or

inferior crop.

substituted organic ones , and irrigation displaced rainfed cropping. As a result, soils were deprived of

vital organic material , and soil moisture droughts became recurrent. Massive irrigation projects and

water intensive farming, by adding more water to an ecosystem than its drainage system can

accommodate, have led to waterlogging , salinization and desertification.

In India, 10 million hectares of canal irrigated land is waterlogged and no other 25 million hectares is

under the threat of salinization. When waterlogging is recurrent, it is likely to lead to conflict between

farmers and the state. In the Krishna basin, waterlogging at malaprabha irrigation project led to farmer

rebellions. Similarly, the International water treaty, where river Indus flows from China to Pakistan but

most Ladakhisdoesn’t have access to it causes unrest and fights amongst Ladakhis and Kashmiris.

Salinisation is closely related to water logging. The salt poisoning of arable land has been an

inevitable consequence of intensive irrigation and in arid regions. Water scarce locations contain large

amounts of unleached soil, pouring irrigation water into such soils brings the salts to surface. When

the water evaporates, saline residue remains. Today more than one third of the world’s irrigated is salt

polluted. An estimated 70,000 hectares of land in Punjab are salt affected and produce poor yields.

In the Indian village of Kuru, there is no drinking water available to the 600 residents due to

salinization.

Role of women in conservation:

We mostly find in billboards and advertisements, men creating ice stupas or climbing up ice stupas,

artificial glaciers. However, most of the water conservation-related work is mostly done by women.

Especially all the initial work, like carrying water from the zing i.e a pond from a hill to the field and

home along with carving ice stupas is done by them but there is no documentation and no

representation in images, billboards.

Women face many hill-related accidents while bringing water for their homes and fields due to

distance between the reservoir and their homes, fields. Children suffer due to storage of water for a

long time in reservoirs as there can be contamination and infestation.

Even in the traditional Chhorpun system, water is first offered to deities, then ice stupas are created.

Water is the first form of life following which is fish and they also form lord Vishnu’s two life forms. We

have to believe that water is divine and not a property that can be collected and demarcated in or for

one village. Temperament of villages is to not share water with everyone as there could be shortage in their village, I have always engaged in deep dialogue with community to have an open heart and

share resources with each other.

Therefore, more than any other resource, water needs to remain a common good and requires

community management. In fact, in most societies, private ownership of water has been prohibited.

Ancient texts such as the Institute of Justinian show that water and other natural sources are public

goods: “By the law of nature, these things are common to mankind – the air, running water, the sea

and consequently the shore of the sea.

Water is a moving, wandering thing and must of necessity continue to be common by the law of

nature. Wrote Williams Blackstone,” so that I can only have a temporary, transient, usufructuary

property therein.”

The emergence of modern water extraction technologies has increased the role of state in water

management. With globalization and privatization of water resources, new efforts to completely erode

people’s rights and replace collective ownership with corporate control are underway. The

communities of real people with real needs exist beyond the state and the market is often forgotten in

the rush for privatization.

Since women are the water providers, disappearing water sources have meant new burdens and

drudgery for them. Each river and spring and well, drying up means longer walks for women collecting

water and implies more work and fewer survival options. In Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat,

Madhya Pradesh and implies more work and fewer survival options. In Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan,

Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, most villages

are facing new water scarcities created by maldevelopment and reductionist science.

Nature’s work and women’s work in water conservation has usually been ignored by the masculinist

The paradigm of water management has replaced community control by privatization and water

prudent staple food crops by water-thirsty cash crops. Women have had a significant productive role

in food cultivation based on water-conserving technologies. They have been central to food

production, based on sustainable use of water, in arid zones. The maldevelopment model which sees

the agricultural output in terms of cash rather than nutritive value has undermined the efficient

production of nutritive crops like jowar and bajra by seeing them as marginal and uneconomic.

Women’s work in producing staple, water-conserving food grains is only one of the many mechanisms

for water conservation; their work in adding organic matter to the soil – from crops, from the cowshed,

from trees and forests – also contributes critically towards conserving water and preventing

desertification.

Women’s work in traditional agriculture has been an effective partnership with nature which increases

water availability for human survival without disrupting the water cycle. This partnership is now being

substituted by a partnership between chemicals and masculinist science and industry. Instead of

water retentivity and soil fertility being increased by organic matter produced by nature and processed

and distributed by women and peasants.

The recovery of the feminine principle in water management consists of recovering the stability of the

water cycle, and recovering the role of women and poor peasants and tribals as water managers for

the use of water for sustenance and not for non-sustainable profits and growth. The recovery of the feminine involves the recognition that sustainable availability of water resources is based on

participation in the water cycle and is then displaced in its process of purification and treatment. For

centuries, nature’s various products and women’s knowledge of their properties have provided the

basis for making water safe for drinking in every home and village of India.

Results and outcome:

Rainwater harvesting and the traditional chhorpun system are native and understandable by the local

population. Glacier recharge is dependent on the climatic conditions hence ice stupas are effective as

designed by Shri Norphelhowever not very predictable. The best solution so far discussed is floating

water pumps to lift water from the river Indus, Takamchik has three ponds and some fields are close

to the water body. We have to revive the resources’ channeling system and draw the pipeline.

Another solution is sharing of water between Takmachik and Domkhar. We also want to create a

system of community water drainage system so washing clothes in river basins is banned. We will lay

more emphasis on growing pseudo cereals and less water-intensive crops to preserve water. We also

understood deeply that water management and water treatment in the western world is a field

dominated by men, but in tropical developing countries women were the actual pacemakers for

traditional water purification. We must give more thought to role of women in the context of new water

supply projects and not just highlighting drudgery. We have to glorify women as not just victims of the

burden of providing water but also for being the source of knowledge and skills for providing safe

water and hence better health for rural areas.

References:

Vandana Shiva (2010). Staying Alive Women, Ecology and Survival in India.

Vandana Shiva (2002). Water Wars Privatization, Pollution and Profit

we are to preserve and

we are to preserve and